Neurobiological Foundations of Human Affect

Neurobiological Foundations of Human Affect: A Comprehensive Analysis of the D.O.S.E. Framework and Its Homeostatic Counterparts

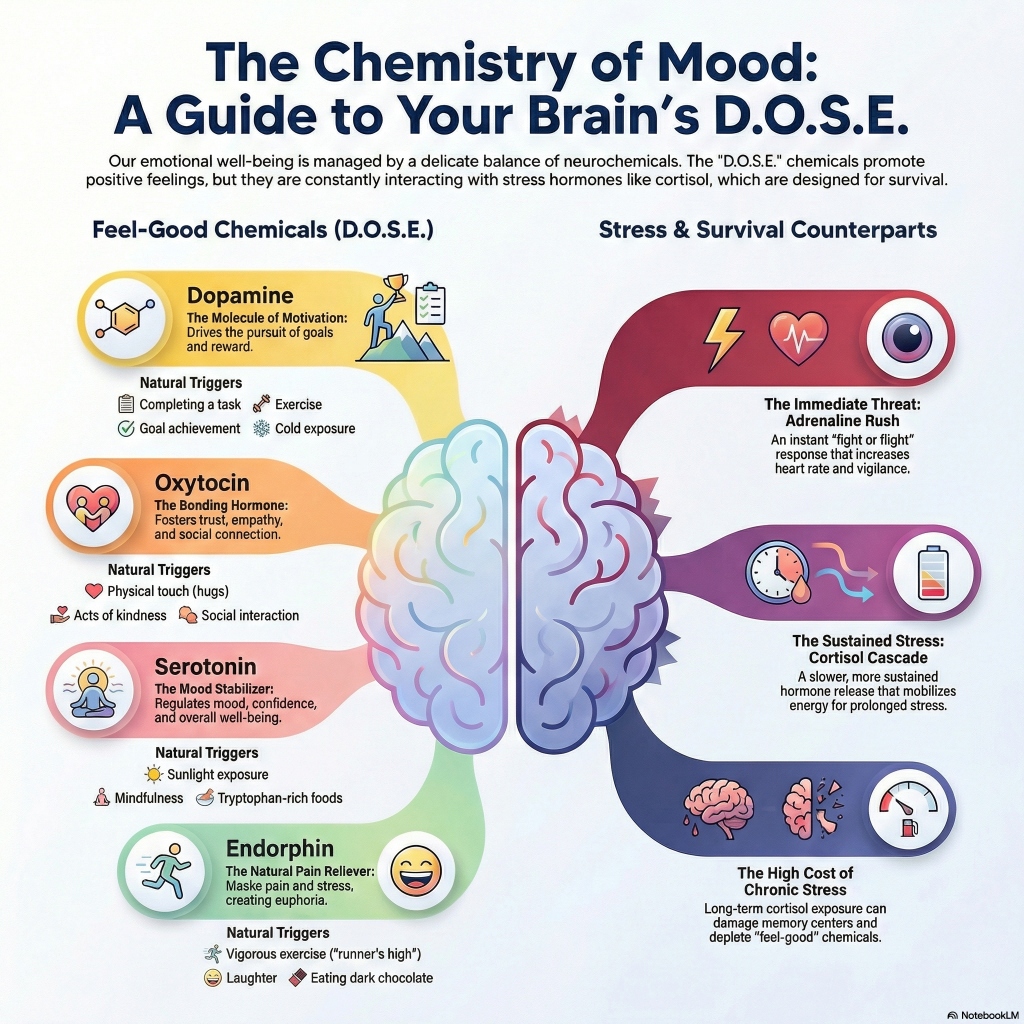

The internal experience of human emotion, motivation, and social connectivity is governed by a sophisticated landscape of neurochemical modulators. Within the discourse of contemporary psychobiology, the acronym D.O.S.E.—representing Dopamine, Oxytocin, Serotonin, and Endorphins—has emerged as a foundational framework for understanding the “happiness chemicals” that facilitate positive affect and adaptive behavior.[1, 2] However, a rigorous scientific examination reveals that these molecules do not operate in isolation; rather, they exist within a delicate homeostatic balance, frequently counter-regulated by stress-related hormones such as cortisol and adrenaline, and metabolic signals like ghrelin and leptin.[3, 4, 5] This report provides an exhaustive analysis of these neurochemical systems, their evolutionary origins, their biochemical mechanics, and the lifestyle interventions required for their optimization.

The Dopaminergic System: Incentive Salience and the Pursuit of Reward

Dopamine is frequently characterized in popular media as a “pleasure molecule,” yet a review of the historical and contemporary literature suggests this is a significant oversimplification. Early research in the 1980s identified that dopamine levels rise in response to rewards like food, leading to the initial pleasure-centric hypothesis.[6] However, subsequent findings in the 1990s and 2000s demonstrated that inhibiting the dopaminergic system in animal models does not diminish the “liking” of a reward, but rather the “wanting” or motivation to seek it out.[6] Consequently, dopamine is more accurately defined as the molecule of incentive salience and the pursuit of reward.[6]

Neuroanatomical Production and Pathways

Dopamine is a catecholamine neurotransmitter synthesized primarily in two adjacent midbrain regions: the ventral tegmental area (VTA) and the substantia nigra.[3] From these sites, it travels along three primary pathways that dictate its functional impact. The mesolimbic pathway, projecting from the VTA to the nucleus accumbens, is the primary driver of the reward system and reinforcement learning.[3, 7] The mesocortical pathway, projecting to the prefrontal cortex, influences executive function, attention, and decision-making.[6, 8] Finally, the nigrostriatal pathway, projecting from the substantia nigra to the striatum, is critical for motor control and movement, the depletion of which is the hallmark of Parkinson’s disease.[6, 7]

Table 1: Dopaminergic Dynamics and Clinical Correlates

| Feature | Specification | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Production Sites | Ventral Tegmental Area (VTA), Substantia Nigra | [3] |

| Primary Pathways | Mesolimbic, Mesocortical, Nigrostriatal | [6, 7] |

| Precursor Amino Acid | L-Tyrosine (synthesized from L-Phenylalanine) | [7, 9, 10] |

| Cofactor Requirements | Iron, Vitamin B6, Zinc, Magnesium, Folate | [11, 12] |

| Mechanism of Action | Incentive salience, reward prediction error, motor initiation | [6, 13] |

| Deficiency States | ADHD, Parkinson’s, Anhedonia, Depression | [6, 7, 14] |

| Natural Triggers | Goal achievement, listening to music, exercise, cold exposure | [3, 9, 15] |

The Effort Paradox and Reinforcement Learning

The dopaminergic system is central to reinforcement learning (RL), the process by which behavior is guided by rewards and punishments.[13, 16] Humans and other mammals utilize dopamine to signal “reward prediction errors”—the discrepancy between an expected outcome and the actual result.[13, 17] When an outcome is better than expected, a dopamine surge reinforces the behavior; when it is worse, a dopamine “dip” encourages avoidance.[16, 18]

Interestingly, research into the “Effort Paradox” suggests that dopamine also helps humans value effort itself. While humans typically avoid unnecessary exertion, tasks can be perceived as more rewarding if they require a degree of challenge.[6] A landmark study at Stanford University showed that increasing the difficulty of a task actually increased dopamine release in the striatum of mice, suggesting that the pursuit of a difficult goal can become intrinsically rewarding.[6] This mechanism explains why individuals seek out marathons or complex puzzles even in the absence of an external reward.[6]

Serotonin: The Regulatory Stabilizer and Mood Modulator

Serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, or 5-HT) is the primary neurotransmitter responsible for emotional stabilization and homeostasis.[9, 19] It regulates a vast array of physiological functions, including sleep architecture, appetite, digestion, and cognitive processes like memory and learning.[2, 3, 7] While it is a critical modulator in the brain, approximately 80% to 90% of the body’s serotonin is produced in the gastrointestinal tract, specifically by enterochromaffin cells in the gut microbiome.[1, 3] This spatial distribution underscores the importance of the gut-brain axis, where hunger and digestive health directly influence emotional stability.[1, 7]

Biochemical Synthesis and the Kynurenine Shunt

The synthesis of serotonin is a two-step process initiated by the hydroxylation of the essential amino acid tryptophan into 5-hydroxytryptophan (5-HTP), catalyzed by the rate-limiting enzyme tryptophan hydroxylase (TPH).[20, 21] There are two isoforms of this enzyme: TPH1, found primarily in the periphery (gut and pineal gland), and TPH2, which is specific to neurons in the brainstem’s raphe nuclei.[20, 22]

Serotonin availability is highly sensitive to external stressors. Under conditions of chronic stress or systemic inflammation, the body activates the kynurenine pathway, which shunts tryptophan away from serotonin synthesis.[20, 23] This redirection is driven by enzymes like indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO) and tryptophan 2,3-dioxygenase (TDO), which are induced by pro-inflammatory cytokines and glucocorticoids like cortisol.[20] This metabolic shift explains why chronic stress often leads to a biological depletion of serotonin, manifesting as depression and anxiety.[20, 23]

Table 2: Serotonergic Metabolism and Regulatory Functions

| Category | Details | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Site of Synthesis | Gastrointestinal Tract (80-90%), Raphe Nuclei | [1, 3] |

| Rate-Limiting Enzyme | Tryptophan Hydroxylase (TPH2 in brain) | [20, 21, 23] |

| Functional Role | Mood stabilization, rejection sensitivity, sleep regulation | [1, 9, 19] |

| Clinical Interventions | SSRIs, MAOIs, Tryptophan-rich diet | [7, 9, 22] |

| Genetic Influences | TPH2 polymorphisms, Serotonin Transporter (s-type) variant | [21, 24, 25] |

| Stress Interaction | Cortisol-induced kynurenine shunt (tryptophan depletion) | [20, 23] |

Serotonin and Social Hierarchy

In addition to its role in mood, serotonin is often referred to as the “confidence molecule”.[1] Research has demonstrated that high levels of serotonin are correlated with lower sensitivity to social rejection.[1] This allows individuals to place themselves in social situations that can enhance their self-esteem and social standing.[1] Conversely, low serotonin levels are associated with “harm-avoidance” behaviors and oversensitivity to social threats.[26] Pharmacological manipulations in humans have shown that increasing serotonin levels can enhance punishment learning and sensitivity, suggesting that serotonin helps the brain navigate costs and avoid negative outcomes, acting as a functional counterbalance to dopamine’s focus on rewards.[13, 16]

Oxytocin and Vasopressin: The Social and Affiliative Axis

Oxytocin, frequently dubbed the “love hormone,” is a neuropeptide synthesized in the hypothalamus and released by the posterior pituitary gland.[3, 9, 27] While its peripheral roles in childbirth and lactation are well-established, its central functions in the brain are critical for social cohesion, trust, and empathy.[1, 3, 7] However, modern neuroendocrinology views oxytocin as part of an integrated “OT-VP” pathway that also includes vasopressin, its evolutionary cousin.[28, 29]

Evolutionary Dynamics: Trust vs. Defense

The oxytocin and vasopressin systems evolved from a single ancestral gene to manage the complex needs of mammalian sociality.[28, 29] In a context of perceived safety, oxytocin dominates, facilitating “immobility without fear”—a biological state necessary for nursing, social grooming, and sexual intimacy.[28] In contrast, vasopressin is primarily associated with defensive behaviors, including mobilization, territorial aggression, and mate-guarding, particularly in males.[27, 28, 30]

Amygdala Modulation and Social Salience

One of the most profound effects of oxytocin is its ability to inhibit the activity of the amygdala, the brain’s primary threat detection center.[26] By reducing amygdala activation, oxytocin decreases social anxiety and promotes approach behavior.[26] However, oxytocin does not simply “make people nice”; it increases the “salience” or psychological importance of social cues.[27, 31] This means that while it can enhance trust in safe environments, it can also intensify the memory of negative social interactions.[1, 31] For example, studies have shown that oxytocin can reinforce negative social memories if the initial bonding experience was traumatic or characterized by rejection.[1]

Table 3: Comparison of the Neurohypophyseal Peptides

| Peptide | Primary Context | Behavioral Effect | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Oxytocin | Perceived Safety | Trust, nurturing, bond formation, “Tend and Befriend” | [9, 28, 31] |

| Vasopressin | Perceived Threat | Territoriality, mobilization, aggression, defense | [27, 28, 30] |

| Interaction | Homeostasis | OT can override VP to facilitate social reward | [28, 29] |

Mutual Interactions with Serotonin

The oxytocin and serotonin systems exhibit significant reciprocal modulation. Serotonergic neurons in the raphe nuclei possess oxytocin receptors, and oxytocin administration has been found to inhibit serotonin signaling in the dorsal raphe nucleus (DRN).[26] This inhibitory regulation may explain how oxytocin reduces the defensive “harm-avoidance” typically mediated by serotonin, facilitating closer social proximity.[26] Conversely, serotonin can modulate oxytocin release by interacting with various 5-HT receptors in the hypothalamus, highlighting a deep functional coupling between these two systems for emotional management.[26]

Endorphins: Endogenous Opioids and Pain Suppression

Endorphins (endogenous morphines) are inhibitory neuropeptides produced by the pituitary gland and the hypothalamus in response to pain or stress.[1, 2, 14] Their primary evolutionary function is to mask physical discomfort, allowing an organism to continue its “fight or flight” response despite injury.[1, 14]

Mechanics of the “Natural High”

Endorphins function by binding to mu-opioid receptors in the central nervous system, which inhibits the release of proteins involved in pain signaling.[32] This binding also triggers a downstream release of dopamine in the brain’s reward centers, which creates the sensation of euphoria often referred to as the “runner’s high”.[14, 32] However, it is important to note that while endorphins contribute to this state, current research suggests that endocannabinoids like anandamide are also major contributors to post-exercise bliss, as they cross the blood-brain barrier more easily than large endorphin molecules.[33]

Clinical Significance of Endorphin Deficiency

A deficiency in the endorphin system is linked to several chronic conditions characterized by a lack of pleasure (anhedonia) or heightened sensitivity to pain.[14, 34] Conditions such as fibromyalgia, chronic migraines, and treatment-resistant depression have been correlated with low endorphin levels.[14, 32] Furthermore, maladaptive behaviors like self-harm or exercise addiction can be understood as desperate attempts to trigger an endorphin release to cope with emotional distress.[14]

Table 4: Endorphin Triggers and Deficiency Symptoms

| Category | Details | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Production Sites | Pituitary Gland, Hypothalamus | [3, 14] |

| Natural Boosters | Vigorous exercise, laughter, dark chocolate, spicy foods, sex | [2, 14, 19] |

| Primary Receptors | Mu-Opioid Receptors | [32] |

| Deficiency Symptoms | Anxiety, chronic pain, depression, sleep issues, addiction | [14, 32, 34] |

| Key Function | Pain masking, stress reduction, self-esteem boost | [1, 14, 19] |

The Counterparts: The Neurobiology of Stress and Survival

The D.O.S.E. framework focuses on chemicals associated with positive states, but these are constantly in flux with the body’s primary stress-response systems: the Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) axis and the Sympathetic-Adrenal-Medullary (SAM) system.[4, 35]

The SAM System: Immediate Reaction

When a threat is detected, the SAM system provides an immediate response within seconds. The sympathetic nervous system triggers the adrenal medulla to release catecholamines—adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine).[4, 35] These hormones cause rapid physiological changes: increased heart rate, dilated pupils, and the mobilization of blood flow to skeletal muscles, preparing the body for immediate action.[4, 35, 36]

The HPA Axis: Sustained Response

The HPA axis follows the SAM response, providing a slower but more sustained reaction to stress. The hypothalamus releases corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which signals the pituitary to release adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), eventually prompting the adrenal cortex to secrete cortisol.[35, 37] Cortisol acts as a glucocorticoid, mobilizing glucose stored in the liver to provide the constant energy supply needed for prolonged stressors.[35]

The Consequences of Chronic Cortisol

Under normal conditions, the HPA axis is self-regulating via a negative feedback loop: high cortisol levels trigger receptors in the hypothalamus and hippocampus to stop the production of CRH.[35, 37] However, chronic stress can desensitize these receptors, leading to persistent hypercortisolemia.[4, 37] This sustained exposure is neurotoxic, particularly to the hippocampus, where it interferes with synaptic plasticity and suppresses neurogenesis—the birth of new neurons.[38, 39, 40]

Long-term cortisol elevation has been linked to:

- Hippocampal Atrophy: A reduction in hippocampal volume, leading to memory deficits and cognitive impairment.[38, 40]

- Serotonin Depletion: Through the aforementioned kynurenine shunt.[20]

- Dopamine Disruption: Excessive cortisol can blunt the reward system, leading to anhedonia and lack of motivation.[7]

Table 5: Hormonal Interactions in the Stress Response

| System | Hormones Involved | Timeframe | Primary Effect | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAM | Adrenaline, Norepinephrine | Seconds | Increased heart rate, vigilance, rapid action | [35] |

| HPA | CRH, ACTH, Cortisol | Minutes/Hours | Glucose mobilization, sustained energy | [35] |

| Feedback | Cortisol receptors | Negative Loop | Returns body to homeostasis | [35, 37] |

Metabolic Counterparts: Ghrelin and Leptin in the Stress Cycle

The regulation of mood and stress is deeply intertwined with energy metabolism. Ghrelin and leptin, the two primary hormones involved in appetite regulation, act as critical bridges between stressful life events and biological states.[5, 41]

- Ghrelin: The Hunger-Stress Link: Ghrelin, known as the “hunger hormone,” is produced in the stomach and stimulates appetite by signaling to the arcuate nucleus in the hypothalamus.[41, 42] Research indicates that stressors—particularly those involving interpersonal tension or social defeat—can significantly increase ghrelin production.[5, 43] Elevated ghrelin levels not only stimulate hunger but can also increase food cravings and reward-driven eating behaviors, as the brain seeks the comfort of palatable foods to mitigate stress signals.[42, 44]

- Leptin: Satiety and Mood Prediction: Leptin is secreted by adipose (fat) tissue and signals satiety, or “fullness,” to the brain.[41, 42] While its primary role is energy balance, it also plays a role in mood regulation. In animal models, leptin administration has shown anxiolytic and antidepressant effects.[41] However, in humans, the relationship is more complex. Chronic stress can lead to “leptin resistance,” where individuals have high circulating levels of the hormone but the brain fails to receive the satiety signal.[42, 44] Interestingly, longitudinal studies have shown that high leptin levels, often associated with abdominal adiposity, are a risk factor for developing depressed mood over time.[41]

The Excitatory and Inhibitory Balance: Glutamate and GABA

Underpinning all neurochemical activity is the balance between the two most abundant neurotransmitters in the central nervous system: glutamate and gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA).[45]

Glutamate: The Primary Excitement

Glutamate is the brain’s primary excitatory neurotransmitter, facilitating nearly all fast synaptic transmissions.[45, 46] It is essential for synaptic plasticity, learning, and the modulation of neuroendocrine function.[45] However, excessive glutamate can be dangerous. During severe stress, excessive glutamate release can lead to excitotoxicity, contributing to neuronal damage in areas like the hippocampus.[45, 47]

GABA: The Calming Brake

GABA is the primary inhibitory neurotransmitter, acting to reduce neuronal excitability and maintain stability in neural circuits.[45] It is synthesized from glutamate via the enzyme glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), a conversion process that requires vitamin B6 (pyridoxal phosphate) as a vital cofactor.[10, 45] In the context of stress, GABAergic neurons in the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis and the hypothalamus provide a critical inhibitory “gate” that blunts ACTH secretion and prevents the overactivation of the HPA axis.[47]

Table 6: The Glutamate-GABA Dyad

| Neurotransmitter | Role | Clinical Application | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Glutamate | Excitatory; Learning & Memory | Ketamine (NMDA modulator) for depression | [45, 46] |

| GABA | Inhibitory; Relaxation | Benzodiazepines, Pregabalin for anxiety | [10, 45] |

| Balance | Homeostasis | Imbalance linked to epilepsy, bipolar, and MDD | [45, 46] |

Optimization Strategies: Engineering the D.O.S.E. Response

Given the intricate mechanics of these systems, individuals can utilize evidence-based lifestyle interventions to naturally optimize their neurochemical balance and mitigate the detrimental effects of stress hormones.

Nutritional Precursors and Micronutrient Cofactors

The synthesis of dopamine and serotonin is entirely dependent on the availability of precursor amino acids and micronutrient cofactors. For example, the conversion of tryptophan to serotonin requires not only the amino acid itself but also iron, folate, vitamin B3, vitamin C, and vitamin B6.[10, 11]

Table 7: Essential Nutrients for Neurochemical Synthesis

| Nutrient | Target Neurochemical | Food Sources | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vitamin B6 | Serotonin, Dopamine, GABA | Poultry, beef, fish, spinach, eggs | [11, 12] |

| Magnesium | Serotonin, Dopamine, GABA | Nuts, seeds, whole grains, leafy greens | [10, 48] |

| Zinc | Serotonin, GABA | Oysters, red meat, poultry, seeds | [10, 11] |

| Iron | Serotonin, Dopamine | Red meat, lentils, organ meats | [11, 12] |

| Omega-3 (DHA) | Cell Membrane Fluidity | Fatty fish (salmon, sardines) | [11, 12] |

Environmental and Behavioral Interventions

Beyond nutrition, specific behavioral modifications can trigger the release of D.O.S.E. chemicals and suppress cortisol:

- Sunlight Exposure: 10–15 minutes of direct sunlight stimulates the production of serotonin through ultraviolet radiation.[2, 9]

- Deliberate Cold Exposure: Immersing the body in cold water (<59°F) triggers a prolonged release of dopamine, which can stay elevated for several hours.[15, 49] This practice also increases norepinephrine, enhancing focus and resilience.[15]

- Mindfulness and Meditation: Regular meditation has been shown to decrease cortisol levels and increase both serotonin and endorphin production, fostering emotional resilience.[9, 50, 51]

- Social Connectivity: Physical touch, acts of kindness, and positive interactions with pets or loved ones are the most effective ways to trigger oxytocin release.[3, 9, 33]

- Vigorous Exercise: High-intensity exercise triggers a multi-hormonal surge, boosting dopamine for motivation, serotonin for mood, and endorphins for pain relief.[2, 3, 7]

Deconstructing the “Hormone Myth” and Scientific Critiques

While the concepts of D.O.S.E. and stress management are scientifically grounded, it is vital to differentiate empirical evidence from popular pseudoscience. The notion that individuals can “drain” their dopamine through phone usage and need a “dopamine fast” is not supported by neurobiology.[6] Dopamine is an ancient, conserved molecule essential for basic survival; it does not simply disappear because of digital habits.[6] Instead, digital addiction involves the desensitization of reward receptors, not a lack of the molecule itself.[6]

Similarly, the “Hormone Myth” critique warns against over-attributing all female emotional variability to reproductive hormones like estrogen or progesterone.[52] A large body of research shows that for the majority of women, these fluctuating hormones do not cause mental disorders; social, environmental, and interpersonal stressors are far more significant predictors of emotional health.[52]

Conclusion: The Integrated Homeostatic Landscape

The neurochemistry of human affect is a complex, bi-directional flow between hormones, neurotransmitters, and external behavior. The D.O.S.E. framework provides a valuable entry point for understanding the pursuit of reward, the stability of mood, the bond of social connection, and the relief of pain. However, these systems are constantly mediated by the survival-oriented HPA axis and the metabolic signaling of the gut-brain axis.

True psychological resilience is not achieved by chasing “rushes” of any single chemical, but by maintaining the structural integrity of the brain through proper nutrition, adequate sleep, controlled stressors, and meaningful social engagement. By understanding the enzymatic pathways of serotonin, the effort paradox of dopamine, the salience-tuning of oxytocin, and the neurotoxic potential of chronic cortisol, clinicians and individuals alike can develop more effective strategies for mental health and cognitive longevity. The future of psychobiology lies in the further elucidation of these interconnected pathways, moving toward a personalized approach to neurochemical optimization.

- D.O.S.E. : The brain’s happy chemicals, explained. - Khiron Clinics

- Happy Hormones: What They Are and How to Boost Them - Healthline

- Dopamine, serotonin, endorphins, oxytocin: Your happy hormones …

- Stress and Your Body

- Interpersonal Stressors Predict Ghrelin and Leptin Levels in Women - PMC

- Here’s what dopamine, the ‘happy hormone,’ actually does | National …

- Brain Happiness Chemicals: How to Boost Your Feel-Good Hormones Naturally

- The Six Systems (Personality Model) - The Behavioral Scientist

- The happy hormones: your daily dose of feel-good - Chartered Accountants Ireland

- Nutrients That Support the Brain and Mental Wellbeing - Kirily Thomas

- The Role of Micronutrients in Mental Health - Metabolic Psychology

- Unveiling the mechanistic nexus: how micronutrient enrichment shapes brain function, and cognitive health - PubMed Central

- Differential effects of dopamine and serotonin on reward and punishment processes in humans: A systematic review and meta-analys - bioRxiv

- Endorphins: What They Are and How to Boost Them - Cleveland Clinic

- The Science & Use of Cold Exposure for Health & Performance - Huberman Lab

- Dopamine and serotonin differentially associated with reward and punishment processes in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis - PubMed Central

- Differential effects of dopamine and serotonin on reward and punishment processes in humans - bioRxiv

- Differential effects of dopamine and serotonin on reward and punishment processes in humans: A systematic review and meta-analysis | bioRxiv

- Four Happy Hormones - Parkinsons NSW

- Tryptophan Metabolic Pathways and Brain Serotonergic … - Frontiers

- Advances in Tryptophan Hydroxylase-2 Gene Expression Regulation: New Insights into Serotonin-Stress Interaction and Clinical Implications

- Tryptophan Hydroxylase-2: An Emerging Therapeutic Target for Stress Disorders - PMC

- Influence of Tryptophan and Serotonin on Mood and Cognition with a Possible Role of the Gut-Brain Axis - PMC - PubMed Central

- Hippocampal Neurogenesis: Regulation by Stress and Antidepressants - PubMed Central

- Chronic Stress Effects on Hippocampal Structure and Synaptic Function: Relevance for Depression and Normalization by Anti-Glucocorticoid Treatment - Frontiers

- Switching brain serotonin with oxytocin - PMC

- Oxytocin, Vasopressin, and Social Behavior: From Neural Circuits to Clinical Opportunities

- The Oxytocin–Vasopressin Pathway in the Context of Love and Fear

- Editorial comment: Oxytocin, vasopressin and social behavior - PMC - PubMed Central

- Vasopressin and oxytocin receptor systems in the brain: sex differences and sex-specific regulation of social behavior - PubMed Central

- Oxytocin, cortisol, and cognitive control during acute and naturalistic stress - PMC - NIH

- Endorphins: Natural Pain and Stress Relievers - Verywell Health

- The Neurochemicals of Happiness | Psychology Today

- Endorphins: Effects and how to boost them - Medical News Today

- Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis - Simply Psychology

- Stress and Your Body | Psychological & Counseling Services - University of New Hampshire

- Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis: What It Is - Cleveland Clinic

- Analyzing The Impact Of Chronic Stress On Hippocampal Function A Systematic Review

- Effects of Chronic Stress on Structure and Cell Function in Rat Hippocampus and Hypothalamus - Taylor & Francis Online

- Stress effects on the hippocampus: a critical review - PMC - PubMed Central - NIH

- Mood disorders: A potential link between ghrelin and leptin on human body? - PMC

- Hormones and Weight Gain: Cortisol, Leptin, and Ghrelin - Rachel Trotta

- Interpersonal stressors predict ghrelin and leptin levels in women - The Ohio State University Wexner Medical Center

- Stress, cortisol, and other appetite-related hormones: Prospective prediction of 6-month changes in food cravings and weight - PubMed Central

- GABA and Glutamate: Balancing Inhibitory & Excitatory Signals - Creative Proteomics

- Glutamate and GABA Homeostasis and Neurometabolism … - Frontiers

- Role of GABA and Glutamate Circuitry in Hypothalamo Pituitary Adrenocortical Stress Integration | Request PDF - ResearchGate

- Role of Vitamins and Minerals on Neurotransmitters | Blog - TalktoAngel

- Episode 232: Cold Exposure for Mental Health - Psychiatry & Psychotherapy Podcast

- 8 key factors behind the production of happiness hormones - Samitivej Hospital

- Biohacks for Beginners: Meditation, Intermittent Fasting, Cold Therapy and More

- The Hormone Myth