Foundations of Behavioral Design

Foundations of Behavioral Design: A Comprehensive Analysis of Octalysis, Hook, and MDA Frameworks

The evolution of digital interaction has transitioned from a paradigm of function-focused design to one of human-focused design. In traditional systems, functionality and efficiency are prioritized, operating under the assumption that users will perform tasks simply because they are required or because the system facilitates a specific outcome.[1, 2] However, human-focused design acknowledges that individuals are not purely rational actors; they are driven by complex emotional landscapes, insecurities, and varying degrees of intrinsic and extrinsic motivation.[2] This shift has necessitated the development of sophisticated behavioral design frameworks that allow creators to structure experiences—whether in games, software as a service (SaaS), or educational platforms—to optimize for long-term engagement and psychological well-being.[3]

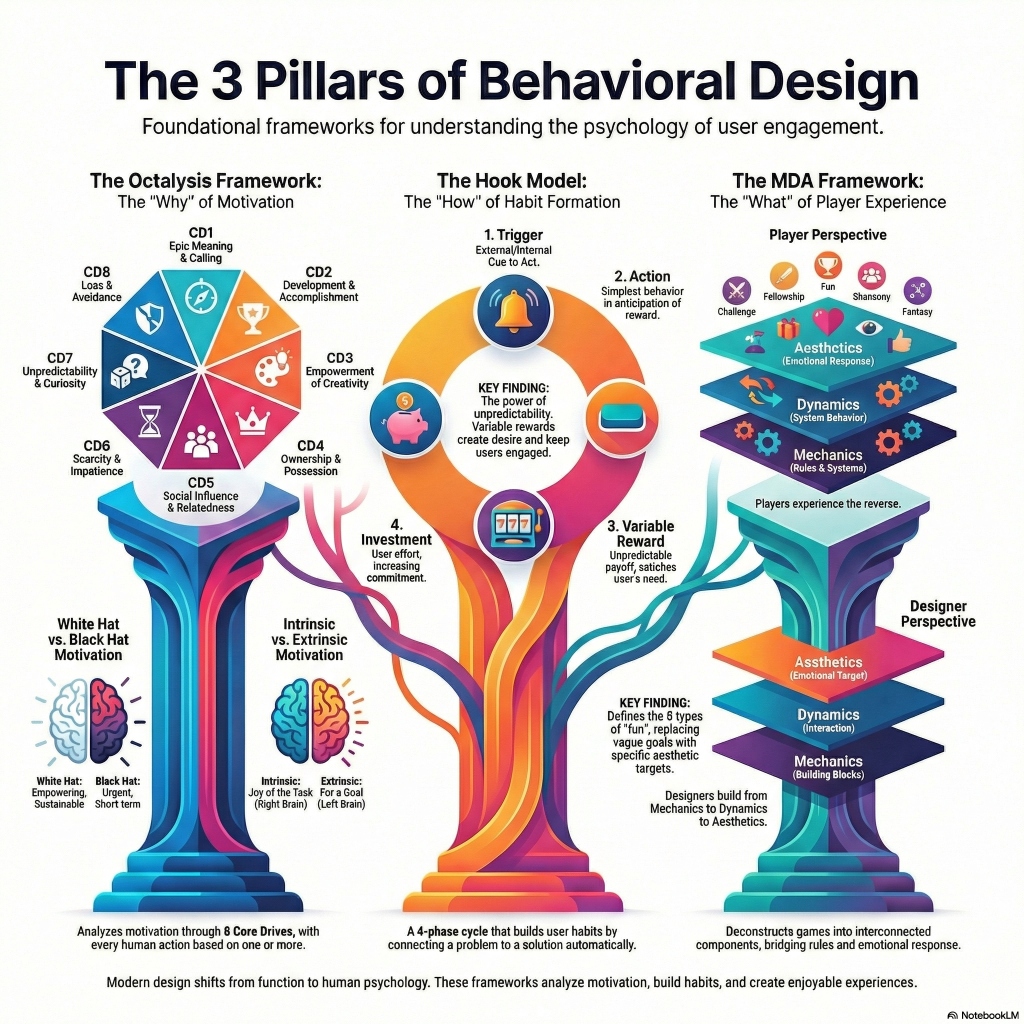

The three pillars of this behavioral design discipline are the Octalysis Framework, the Hook Model, and the Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics (MDA) Framework. Each offers a unique perspective on the construction of habit-forming and engaging experiences. Octalysis provides a holistic view of human motivation through eight core drives, distinguishing between positive “White Hat” motivators and urgent “Black Hat” motivators.[4, 5] The Hook Model details a four-stage process for habit formation, focusing on the cyclical nature of triggers, actions, and rewards.[6, 7] Finally, the MDA Framework bridges the gap between technical rules and emotional outcomes, allowing designers to predict how mechanical systems will manifest as aesthetic experiences.[8, 9]

The Octalysis Framework: A Taxonomy of Human Motivation

Developed by Yu-kai Chou, the Octalysis Framework is an integrative model that analyzes the driving forces behind all human activity.[2, 10] It posits that every action a person takes is rooted in one or more of eight core drives.[2] If none of these drives are present, there is no motivation, and consequently, no behavior occurs.[5, 11] The framework is represented by an octagon, which categorizes drives based on their psychological impact and the nature of the motivation they inspire.[1, 12]

The Eight Core Drives of Human Behavior

The framework decomposes motivation into eight distinct categories, each serving a specific psychological function within a user’s journey.

| Core Drive | Name | Motivation Type | Psychological Basis |

|---|---|---|---|

| CD1 | Epic Meaning & Calling | White Hat / Right Brain | The belief that one is part of something larger or has been “chosen” for a mission.[2, 13] |

| CD2 | Development & Accomplishment | White Hat / Left Brain | The internal drive to make progress, develop skills, and overcome meaningful challenges.[12, 13] |

| CD3 | Empowerment of Creativity & Feedback | White Hat / Right Brain | The engagement in a creative process where users experiment and see immediate results.[11, 13] |

| CD4 | Ownership & Possession | Left Brain | The desire to improve, protect, and accumulate what one owns or has invested in.[12, 14] |

| CD5 | Social Influence & Relatedness | Right Brain | The social elements that drive behavior, including mentorship, acceptance, competition, and envy.[2, 12] |

| CD6 | Scarcity & Impatience | Black Hat / Left Brain | The drive to want something simply because it is difficult to obtain or unavailable.[12, 13] |

| CD7 | Unpredictability & Curiosity | Black Hat / Right Brain | The desire to find out what happens next, driven by uncertainty and the thrill of discovery.[2, 12] |

| CD8 | Loss & Avoidance | Black Hat | The motivation to avoid negative consequences or the loss of previous progress.[2] |

Core Drive 1: Epic Meaning and Calling

Epic Meaning and Calling involves the perception that one’s actions contribute to a greater purpose. This drive is often leveraged in open-source projects like Wikipedia, where users dedicate significant time to maintaining a community resource without financial compensation.[12, 13] It also manifests in the “Beginner’s Luck” effect, where individuals believe they possess a unique gift or were “lucky” to receive a rare item early in their journey, compelling them to continue to justify this perceived selection.[2, 13] In the context of business, communicating that a product serves a noble cause can provide a sense of purpose even before the user signs up.[4]

Core Drive 2: Development and Accomplishment

This drive focuses on progress and the mastery of skills. It is the most common drive utilized in gamified systems, often through “PBL” elements: points, badges, and leaderboards.[12] However, a critical nuance in this drive is the necessity of “challenge”.[12, 13] Trophies or badges awarded without a corresponding difficulty are perceived as meaningless and fail to provide the sense of accomplishment required to sustain behavior.[12, 13] Development and Accomplishment serve as the primary motivators in educational platforms like Duolingo, where progress bars and streaks signify mastery.[10]

Core Drive 3: Empowerment of Creativity and Feedback

Considered the “holy grail” of engagement, this drive focuses on intrinsic motivation by providing a dynamic environment where users can use strategy and autonomy.[4] It encourages users to try different combinations and see the results of their creativity.[2, 13] Products like LEGO or games like Minecraft are examples of “Evergreen Mechanics” because the designer does not need to continuously add content; the users find the process of creation inherently rewarding.[12] This drive is essential in the “Endgame” phase of a product to retain long-term users through meaningful choices and autonomous play.[4]

Core Drive 4: Ownership and Possession

Ownership motivation stems from the desire to accumulate wealth or improve one’s virtual assets.[12] When users spend time customizing an avatar or building a profile, they feel a heightened sense of ownership, making them more committed to the platform.[2, 12] This is further amplified by the “Alfred Effect,” where a system that continuously learns about a user’s preferences becomes so personalized that the user feels a sense of attachment and is reluctant to switch to a competitor.[11]

Core Drive 5: Social Influence and Relatedness

This drive encompasses the social forces that influence human behavior, ranging from companionship and mentorship to competition and envy.[2, 12] Seeing a friend achieve a high skill level or own a rare item drives an individual to reach that same level.[2] Relatedness also includes nostalgic triggers, where products that remind users of their childhood increase the likelihood of engagement.[2, 12]

Core Drive 6: Scarcity and Impatience

Scarcity is the drive of “wanting something because you can’t have it”.[12, 13] Designers implement “Appointment Dynamics,” such as requiring a user to return in two hours to collect a reward, to keep the product at the forefront of the user’s mind.[12, 13] A historical example of this drive is the early rollout of Facebook, which was initially exclusive to Harvard students, then elite universities, creating a powerful desire among others to join once it finally opened to the public.[12]

Core Drive 7: Unpredictability and Curiosity

This drive focuses on the excitement of surprise and the unknown.[2] It keeps the brain engaged because the user does not know what will happen next.[2] While this is a harmless driver in movies or novels, it is also the primary psychological mechanism behind gambling addiction.[2] In digital design, variable rewards and mystery boxes utilize CD7 to maintain high levels of engagement.[2, 15]

Core Drive 8: Loss and Avoidance

Loss avoidance is the motivation to prevent negative outcomes. In a minor sense, it involves avoiding the loss of previous work; on a larger scale, it involves the “Sunk Cost Prison,” where a user continues an activity simply to avoid admitting that the time and effort invested thus far were wasted.[2, 4] FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) also falls under this category, as users feel compelled to act on opportunities that may disappear forever.[2]

Dualistic Categorization: Brain Sides and Hat Colors

The Octalysis Framework provides two additional layers of analysis that are critical for balancing a system: the Left/Right Brain dichotomy and the White/Black Hat distinction.[4, 16]

Left Brain vs. Right Brain (Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic)

The Left Brain Core Drives (CD2, CD4, CD6) are associated with logic, ownership, and analytical thought.[16] These are generally “extrinsic” motivators, meaning the user is motivated by the promise of a reward or the attainment of a goal rather than the activity itself.[16] Conversely, the Right Brain Core Drives (CD3, CD5, CD7) focus on creativity, sociality, and curiosity.[16] These are “intrinsic” motivators where the activity is its own reward.[16]

| Dimension | Left Brain | Right Brain |

|---|---|---|

| Focus | Results, Goals, Ownership [16] | Process, Journey, Social [16] |

| Motivation | Extrinsic (Carrot and Stick) [17] | Intrinsic (Fun, Self-Expression) [17] |

| Sustainability | Short-term boost; risk of burnout [17] | Long-term engagement; evergreen [12] |

White Hat vs. Black Hat (Empowerment vs. Urgency)

White Hat motivators (CD1, CD2, CD3) make users feel powerful, satisfied, and in control.[4] While they create a continuous sense of well-being, they lack urgency.[4] A user may feel that an activity is meaningful but may not feel compelled to act immediately.[4] Black Hat motivators (CD6, CD7, CD8) create urgency, obsession, and addiction.[4] While they are highly effective at driving immediate behavior, they often leave users feeling manipulated and stressed in the long run, eventually leading to burnout and system abandonment.[4]

The Hook Model: A Blueprint for Habitual Engagement

While Octalysis provides the psychological “why” of motivation, the Hook Model, developed by Nir Eyal, provides a “how” for habit formation.[6, 18] A habit is defined as a pattern of behavior replicated frequently and performed with little or no conscious thought.[19, 20] The Hook Model suggests that habit-forming products move users through a four-phase cycle: Trigger, Action, Variable Reward, and Investment.[6, 7]

The Four Stages of the Hook

The cycle is designed to connect a user’s problem to a company’s solution with sufficient frequency to turn engagement into an ongoing practice.[18]

| Stage | Definition | Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Trigger | The actuator of behavior.[14] | Transition from external cues to internal emotional prompts.[6, 14] |

| Action | The simplest behavior done in anticipation of a reward.[6] | Minimize effort while maximizing motivation (Fogg Model).[14, 21] |

| Variable Reward | The relief of the user’s “itch” or problem.[7] | Create a “wanting” through unpredictability (Dopamine).[14, 15] |

| Investment | Work done by the user that improves the product.[7, 14] | Store value and prime the next trigger.[14, 21] |

Phase 1: The Trigger

Triggers act as the spark plug of the Hooked Model.[14] They start as external cues—emails, push notifications, or icons on a smartphone—that alert the user to take an action.[6, 14, 19] Through repeated cycles, users develop associations with internal triggers, which are linked to pre-existing behaviors and emotions.[14, 18] Eventually, a user who feels lonely may subconsciously open a social media app without needing an external notification.[6]

Phase 2: The Action

The action is the intended behavior following the trigger.[14] To increase the odds of a user taking action, behavioral designers focus on two factors: motivation and ability.[14] Ability is increased by making the action as easy as possible to perform, while motivation is boosted by the promise of the coming reward.[14, 22] In digital games like Candy Crush Saga, the action is the rhythmic “match-three” gameplay, which is simple to execute but increasingly difficult to master.[23]

Phase 3: The Variable Reward

The variable reward is what separates a Hook from a predictable feedback loop.[14] Predictable loops do not create desire; if a user knows exactly what will happen, they have no reason to return.[14, 18] However, variability—inspired by Skinner’s experiments with intermittent reinforcement—creates a “hunting” mood in the brain.[14, 18] Eyal identifies three types of rewards:

- Rewards of the Tribe: Social acceptance and validation.[7]

- Rewards of the Hunt: The search for material resources or information.[7]

- Rewards of the Self: Personal gratification, mastery, and control.[7, 14]

Phase 4: The Investment

The investment stage occurs when the user puts something back into the product: time, data, effort, social capital, or money.[6, 7] Unlike the action phase, where the goal is immediate gratification, the investment phase is about future rewards.[14] Every bit of work the user does—inviting friends, building a virtual base, or learning new features—makes the product more valuable to them and primes the next trigger in the cycle.[7, 14, 21]

The MDA Framework: Formalizing the Game Design Process

The Mechanics-Dynamics-Aesthetics (MDA) framework provides a formal approach to understanding how game designs function.[8, 9] It breaks down the game experience into three components that relate to each other in a specific causal hierarchy.[8, 24]

Decomposing the Layers

From a designer’s perspective, the mechanics generate dynamics, which then generate aesthetics.[8, 9] However, from a player’s perspective, they experience the aesthetics first, then observe the dynamics, and only indirectly interface with the underlying mechanics.[8, 9, 25]

| Component | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanics | The formal rules, algorithms, and data structures. | Card shuffling, spawn points, ammunition limits.[8, 9] |

| Dynamics | The run-time behavior of mechanics in motion. | Bluffing, “camping,” tactical positioning.[9, 26] |

| Aesthetics | The emotional response and “fun” evoked in the player. | Narrative, challenge, fellowship, discovery.[8, 9] |

Mechanics: The Building Blocks

Mechanics are the base components of the game—the rules that define what actions a player can take and how the game state evolves.[8, 26] In a video game, these are enforced by the computer code.[24] For example, the mechanics of a first-person shooter include weapons, ammunition, and spawn points.[9]

Dynamics: Emergent Behavior

Dynamics describe how the mechanics interact with player input and each other during gameplay.[8, 9] This is the “run-time” behavior of the system.[8, 26] A well-known example is “camping” in shooter games, a dynamic where players sit next to a spawn point to immediately kill opponents.[26, 27] While the designer created the “spawn point” mechanic, the “camping” dynamic emerged from how players used that mechanic to achieve victory.[9, 26]

Aesthetics: The Emotional Target

Aesthetics are the desirable emotional responses evoked in the player when they interact with the system.[8, 9] To replace vague terms like “fun,” the framework proposes a taxonomy of eight kinds of fun:

- Sensation: Game as sense-pleasure.[8]

- Fantasy: Game as make-believe.[8]

- Narrative: Game as drama.[8]

- Challenge: Game as obstacle course.[8]

- Fellowship: Game as social framework.[8]

- Discovery: Game as uncharted territory.[8]

- Expression: Game as self-discovery.[8]

- Submission: Game as pastime.[9]

Synthesis: Designing Integrated Behavioral Systems

Effective game and product design requires the synthesis of these frameworks to ensure a balance of immediate urgency and long-term sustainability.[3, 4] The relationship between these frameworks can be understood as a hierarchy of analysis: MDA provides the structural ontology, Octalysis provides the motivational lens, and the Hook Model provides the habitual loop.[3, 25, 28]

The Lifecycle of Engagement

The Octalysis framework maps the user experience across four distinct phases, which aligns with the iterative nature of the Hook Model.[1, 2]

- Discovery Phase: The initial phase where users come across the product.[1] Motivation is often driven by CD7 (Curiosity) or CD1 (Epic Meaning).[4]

- Onboarding Phase: Users learn the rules and tools.[1] Designers often utilize CD2 (Accomplishment) to provide quick wins.[4, 29]

- Scaffolding Phase: The regular journey toward a goal.[1] This is where the Hook Model’s cycles are most frequent, building habits through variable rewards.[4, 14]

- Endgame Phase: How veterans are retained once they have “done everything”.[1] Success here depends on “White Hat” intrinsic motivators like CD3 (Creativity) and CD5 (Social Influence).[4]

Case Study: DreamsCloud and Traction Growth

The application of Octalysis to the platform DreamsCloud demonstrates how behavioral design can drive hard KPIs.[30] By focusing on the Discovery phase through CD1 (communicating that “Dreams Matter”) and the Endgame through CD4 (the Alfred Effect, where the system learned about users over time), DreamsCloud saw unique monthly visitors grow from thousands to over 2 million.[11] This represents a 500-fold increase in traction metrics achieved by shifting from a function-focused design to a human-focused design that accounted for user insecurities and feelings about the significance of their dreams.[2, 11]

Case Study: BitDegree and Learning Sustainability

BitDegree utilized the Octalysis framework to solve the low course completion rates typical of MOOCs.[29] The intervention involved creating a gamified “learning path” where users were assigned characters (Onboarding), met different objectives to earn cryptocurrency (Scaffolding), and engaged in social learning (Endgame).[29] Even with only 20% of the design implemented, course completion rates increased by 400%.[29] This success was attributed to the balance of extrinsic motivators (cryptocurrency rewards) and intrinsic motivators (social learning and character progression).[29]

Mechanical Implementation in Clash of Clans

Clash of Clans provides a robust example of how specific mechanics drive dynamics and aesthetics, satisfying the MDA and Hook frameworks simultaneously.[31]

| Mechanical Element | Dynamic Outcome | Aesthetic / Core Drive |

|---|---|---|

| Upgrade Timers | Subconscious anticipation and repeated check-ins.[31] | CD6: Scarcity / Scaffolding habit.[31] |

| Clan Reinforcements | High-level soldiers donated by allies.[31] | CD5: Social Influence / Fellowship.[14, 31] |

| Random Resource Carts | Surprises when returning to the app.[31] | CD7: Unpredictability / Variable Reward.[14, 31] |

| Base Building | Sunk cost of time and strategy invested.[31] | CD8: Loss Avoidance / Investment.[14, 31] |

The game’s success is rooted in its ability to make the “action” part of the hook seamless while providing endless strategies for buildings and troop formations, ensuring that as players invest more, they find it increasingly difficult to abandon the game.[14, 31]

Ethical Considerations and Psychological Risks

The power of behavioral design to “manufacture desire” raises significant ethical questions.[14, 32] Critics have referred to some gamification practices as “exploitationware,” as they may replace real incentives with fictional ones like points and badges that hold no real value for the worker or user.[33]

The Manipulation Matrix

Nir Eyal provides a tool for designers to evaluate the ethics of their habit-forming products called the Manipulation Matrix.[7, 32]

| Category | Description | Ethical Status |

|---|---|---|

| The Facilitator | The designer builds a product they would use themselves and that improves the user’s life.[7] | Ethical “Sweet Spot”.[7] |

| The Peddler | The designer builds a product they don’t use, but they believe it helps others.[7, 20] | Vulnerable to “resignation”.[34] |

| The Entertainer | The designer builds something fun but doesn’t necessarily claim it improves life.[7] | Artistic/Game focus.[7] |

| The Dealer | The designer builds something they don’t use solely for profit through manipulation.[7, 20] | High risk of exploitation.[34] |

Burnout and the “Bad Taste” of Black Hat

A primary risk of Black Hat gamification (CD6, CD7, CD8) is that it creates compulsion rather than motivation.[35] If users are taking actions to relieve anxiety rather than pursue something they genuinely want, the design has entered “dark territory”.[35] For instance, LinkedIn’s retired “Top Voice Badge” was criticized for creating anxiety around social status rather than celebrating genuine contribution.[35] Overuse of these triggers can lead to psychological fatigue, characterized by a sense of loss of control over one’s own behaviors, similar to a gambling addiction.[2, 4]

Designing for Empowerment (ETHIC Framework)

To mitigate these risks, designers are encouraged to follow principles of empowerment [35]:

- Transparency: Make it clear what actions lead to what outcomes.[35]

- Control: Allow users to opt out of distressing features or take breaks without punishment.[35]

- Balance: Focus on “White Hat” motivators that make users feel powerful and satisfied in the long term.[2, 4]

Mathematical Foundations of Gameplay Dynamics

To move beyond qualitative descriptions, designers often utilize mathematical models to predict dynamic behaviors.[9] For example, the probability of rolling a specific sum on two six-sided dice (2D6) determines the average time it takes a player to progress in games like Monopoly.[9]

The probability of rolling a specific sum can be expressed as:

By understanding these probabilities, designers can calculate the “resource economy” and adjust mechanics—such as introducing “taxes” for wealthy players or “subsidies” for those lagging behind—to maintain the aesthetic of “Challenge” and prevent the “Loss Avoidance” dynamic of a widening leader-gap where only one player remains invested.[9]

Conclusion: The Future of Human-Focused Design

The synthesis of Octalysis, the Hook Model, and the MDA framework provides a comprehensive toolkit for modern designers to build experiences that are not only engaging but also sustainable and ethical.[1] By shifting focus from pure function to the optimization of human motivation, organizations can bridge the gap between things people must do and things they want to do.[1] The future of this discipline lies in its ability to cater to diverse player types—Achievers, Socializers, Explorers, and Killers—while maintaining the psychological well-being of the user throughout their journey.[1, 36] As behavioral science continues to inform technology, the goal remains to make important things more enjoyable and enjoyable things more productive.[1]

- Framework - The Octalysis Group

- Octalysis: The Complete Gamification Framework (8 Core Drives Explained) - Yu-kai Chou

- Gamification Design Frameworks Explained - How to Hook Users?

- White Hat vs Black Hat Gamification in the Octalysis Framework – Yu …

- The art of gamification - Part I - PALTRON

- The Hook Model: Retain Users by Creating Habit-Forming Products - Amplitude

- Understanding the Hook Model: How to Create Habit-Forming Products - Dovetail

- MDA framework - Wikipedia

- MDA: A Formal Approach to Game Design and Game Research

- Gamification: The Octalysis Framework - Flevy.com

- Octalysis Case Study: Yu-kai Chou’s Success with DreamsCloud

- The Octalysis Framework for Gamification & Behavioral Design | by Yu-kai Chou | Medium

- Octalysis: Yu-kai Chou’s Gamification Framework | Founders Network

- 4 Steps to Create Desire: How to Spark Interest and Attraction

- Frequency is the key to building habits into your product | Nir Eyal - Churn FM

- Left Brain (Extrinsic) vs Right Brain (Intrinsic) Core Drives in Gamification - Yu-kai Chou

- Extrinsic vs. Intrinsic Motivation in Gamification Marketing - Gamify

- The Hooked Model: 4 Must-Follow Steps - Artkai

- The Hook Model: How to Form Good Habits - Growth Engineering

- Hooked by Nir Eyal - TechHuman

- Analysis of Clash Royale’s stickiness using Nir Eyal’s Hook Model | by Princess Janf

- Should We Worry About the World Becoming More Addictive? Q&A with Nir Eyal

- Candy Crush Case Study by A.L Bacon on Prezi

- MDA Framework - Deliberate Game Design

- MDA Game Design Framework: Meaning, Model, Examples

- Mechanics, Dynamics & Aesthetics - The Quixotic Engineer

- Designing the Core Dynamics - University XP

- BJ Fogg, Octalysis, and the Hook Model: three frameworks that …

- [Gamification Design: A BitDegree Case Study - - The Octalysis Group](https://octalysisgroup.com/2021/03/gamification-design-a-bitdegree-case-study/

- Gamification Case Studies | $1B+ ROI for Banks, Airlines & Tech Leaders | The Octalysis Group

- How Clash of Clans uses the hook model? | by David Yu - Medium

- Book Review: Hooked by Nir Eyal - Threadline

- More than just a game: ethical issues in gamification

- When do habit-forming products become addictive? | by Aaron Weyenberg - Prototypr

- The ETHIC Framework: Designing Ethical Gamification That Actually Works | by Sam Liberty

- Octalysis Framework - GBL@UZH